Creative Myth 2: Children Are More Creative Than Adults.

“Children are more creative than adults” was part of a survey Mattias Benedek and his team conducted in 2021. They looked into creative myths and almost seventy percent of the respondents believed this claim to be true. So why do so many believe this and what is the evidence that small children aren’t very creative?

Photo by Pavel Danilyuk

Ms. Chen, the headteacher at the St. Patridge School, looks around her classroom. Her eyes wander ever so slowly from the left to the right side of the room. When she stops, Ms. Chen looks at 7-year-old Sarah and asks "How many pieces do I need to cut if you serve 3 apples to 4 people?" Sarah purses her lips and frowns her forehead. A brief pause ensues but then she replies "I won’t cut the apples but I'll make apple juice and serve one glass to each!” Many proud parents can probably share similar anecdotes of unexpected answers by their kids. Children's creativity outdo that of even the most imaginative adults. But, is this truly the case?

The Big Bluff.

It’s December 2011. Behind the stage, Dr. George Land awaits his moment in the spotlight. He takes a final look at his handwritten notes, straightens his jacket, and strides confidently towards the bright light beam in the centre of the podium. George’s imposing stature, huge silver eyebrows and resounding voice fill the entire auditorium. He reveals how NASA approached him to find a measure for the creative potential of prospective astronauts, a research programme he conducted in 1968.

Relishing in his 18 minutes of fame while absorbing the undivided attention of the TEDxTucson audience, George unveils a series of astonishing milestones. His method to identify creative potential was so successful that he decided to apply his approach to a group of 1,600 kids between 3-5 years old and 280,000 adults. His longitude study that lasted several decades came to a surprising conclusion; kids were more creative than adults and that as we grow up creativity declines. These were the results that George Land presented:

Amongst 5 year olds: 98%

Amongst 10 year olds: 30%

Amongst 15 year olds: 12%

Same test given to 280,000 adults (average age of 31): 2%

George Land & Beth Jarman: Genius level of creativity by age

George Land at TEDxTucson, 2011

But here is the kicker. When researcher Elisabeth McClure wrote to NASA, they dismissed the existence of a project with professor George Land. Head Start, another programme George Land claimed to have partnered with, was also unaware of having ever worked together. Researcher and writer Emil Kirkegaard investigated Land’s study claims as well. Again, he was unable to find a single trace of NASA’s research by Land in 1968.

Breakthrough in creativity.

For centuries, creativity was an elusive trait, often seen as an enigmatic and inherited power. However, a breakthrough in creativity training emerged in the 1950’s through the research of Guilford, a psychometrician for the American Air Force during World War Two. Guilford noticed that intellectual capacities, including creativity, did not capture standard IQ tests but could be measured in alternative ways. From this, he developed the Structure of Intellect theory, which introduced influential concepts such as divergent production, today it is commonly known as divergent thinking.

Divergent thinking is the ability to look at a problem, challenge or object and come up with multiple solutions or different ways for it. There are several types for testing divergence. The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) developed by Torrance and Presbury is the most popular test for divergent thinking.

Introduced in 1966, the TTCT was influenced by Guilford's extensive work with divergent thinking activities but it was Torrance and Presbury that standardised the administration and scoring of divergent thinking tasks to create the TTCT assessment method. Although this method requires many elements and subscales, at its core the TTCT describes four critical dimensions to evaluate it:

Fluency; total number of relevant responses

Flexibility; number of different categories of responses

Originality; unusualness of responses

Elaboration; amount of detail in the responses

TTCT has lost some of its edge in the last few years yet the Torrance Test remains highly popular but perhaps more in schools than in research. In 1984 Torrance and Presbury reported that the TTCT had been used in three quarters of all published studies of creativity. Imagine that, a single creativity test that is responsible for 75 percent of research.

Reliability of TTCT.

Despite its popularity, more recent studies call the scoring process daunting. Russell Warne in 2022 wrote “One of the biggest is that TTCT is a nightmare to score. Most psychometric tests can be scored easily because there are a limited number of possible responses people can give. In intelligence tests, for example, there is often as few as one correct answer. A good creativity test prompts a wide variety of responses for each item, which makes scoring TTCT complicated because often it is not possible to foresee every possible response.”

Aside from the onerous nature of scoring the TTCT, more importantly is that there are statistical issues with its marking system. A serious problem is the confounding impact of the total number of relevant responses (fluency). The other scores are reliant on fluency because the number of unique responses (originality) and detailed responses (elaboration) will always be dependent on the number of valid responses (fluency). This artificially inflates correlations among TTCT subscores. Russell concluded that the TTCT does not measure a cohesive psychological trait like “creativity.” Instead it measures a collection of behaviours that don’t have much shared variance with one another.

Ironically, Torrance himself discouraged the use of composite scores for the TTCT and warned that using a single score like a composite score may be misleading because each subscale score has an independent meaning. He neither concluded that his tests assess all dimensions of creativity, nor did he suggest that they should be used alone as a basis for decisions.

Creativity in adolescents.

From 1985 to 2008, Sandra Russ conducted a longitudinal study, 14 different studies were compared. Applying a consistent scale, these studies evaluated the cognitive abilities and emotional expressions of children aged 6 to 10 during five minutes of unstructured play. The findings revealed that over the 23-year period, children's comfort and imagination scores demonstrated improvement, while their organisation and emotional expression remained unchanged. Additionally, there was a decrease in the utilisation of negative imagery by the children.

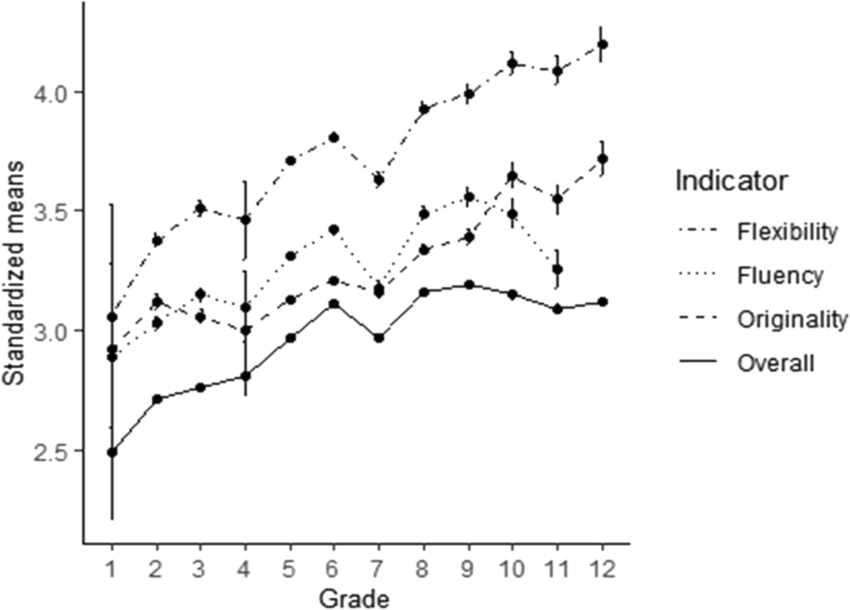

More recently, in 2021, Said-Metwaly led a meta-analysis of creativity tests in children that determined an increase of divergent thinking development from grades 1 to 12: “This study is the first to meta-analyze prior research findings regarding divergent thinking (DT) development from Grades 1 to 12, with a particular emphasis on the widely controversial fourth-grade slump. A total of 2139 standardized means from 41 studies involving 40,918 subjects were analyzed using a meta-analytic three-level model. The findings showed an overall upward developmental trend of DT across grade levels, with some discontinuities.

Specifically, there was no evidence of a general fourth-grade slump; rather, evidence for a seventh-grade slump were found. Moderator analyses indicated that a fourth-grade slump might be observed depending on DT test, task content domain, intellectual giftedness, and country of study. The existence of the seventh-grade slump was also moderated by DT test, task content domain, and gender.

Developmental trends of divergent thinking indicators by grade with corresponding standard errors (Said-Metwaly, Fernández-Castilla, Kyndt, Van den Noortgate, Barbot, 2021)

Creativity as we age.

The decline in creativity as we age is not a universal phenomenon, especially when considering productivity and the generation of original and valuable contributions in fields like science and art. Recent research findings demonstrate a more contextual conclusion.

When we assess creativity based on these factors, output generally increases during our mid-20s, reaches its peak in our late 30s or early 40s, and then gradually diminishes as we grow older. It is during this peak period that individuals often produce their most exceptional work. However, it is important to point out that even as we reach 80 years of age, our expected creative productivity will still be approximately half of what it was at its peak.

But, the relationship between age and creativity is highly dependent on the specific domain of creativity. Different creative pursuits, such as poetry and mathematics, show distinct patterns, with some experiencing early peaks and rapid declines whereas those in history and philosophy tend to have later peaks and more gradual declines.

Added to that the overall productivity of creative individuals varies significantly. On one end of the spectrum, there are "one-hit wonders" who make singular notable contributions, often reaching their creative peak early in their careers. On the other end, there are highly prolific creators who consistently produce numerous contributions, remaining creatively active well into their 60s, 70s, and beyond.

The trajectory of an individual's creative journey is more influenced by their career age than their chronological age. Early bloomers who embark on their creative pursuits at a young age may experience their peak earlier in life, while late bloomers who start their creative pursuit later may encounter their creative peak at a more advanced age. Some late bloomers may not reach their full creative potential until their 60s or 70s, having spent decades working in unfulfilling jobs before uncovering their true passion.

These results reveal that the decline in creativity cannot be attributed exclusively to the ageing of our brains. If this were the case, it would be difficult to explain the variations observed in creative trajectories across different domains, lifetime productivity levels, and the timing of career starts. Late bloomers can reach their creative peaks at ages when early bloomers have already passed their prime. This suggests that it is possible to maintain creativity throughout one's lifespan, offering promising prospects for staying creatively engaged as we grow older.

The Paradox of Creativity.

Over the years, the popular viewpoint has been that creativity is a singular concept, irrespective of the awareness of different behaviours and multiple neural networks associated with it. The oversimplification of the nuanced nature of creativity within a single word and the persistence of outdated information may have inadvertently constrained our understanding of its true complexity and hindered its boundless potential for imagination and innovation.

The dilemma of a composite or overall index becomes evident when evaluating creativity in children. Researchers pointed out that, “young children are more imaginatively creative than adults and yet, also according to current research, creativity's main neural engine is divergent thinking, which relies on memory and logical association, two tasks at which young children underperform adults.” - Fletcher and Benveniste (2022)

How can this be? Creative thinking is often described in divergent thinking terms, and most of today’s assessments of creative thinking have focused on measuring divergent thinking cognitive processes. Yet the literature emphasises that convergent thinking processes, such as analytical and evaluative skills, are essential for creative production as well.

Creativity is not a singular concept that requires imagination only. Creativity requires both novelty (divergence) and logic (convergence). Sarah’s ideas are perhaps more original whereas adults’ ideas tend to be more feasible. Children are less bound by laws, societal norms, and other established knowledge but they underperform in logic and the ability to bring those ideas into reality. As such, children are highly capable of unbounded imagination. This may explain why so many believe that children are more creative than adults.

Perhaps a good approach is to cultivate collaborations between individuals like head teacher Chen and Sarah, taking advantage of their respective strengths to tackle real-world challenges effectively and foster new solutions that combine originality with practicality. By making such collaborations a systemic part of our workplaces, we may unlock the full potential of adults and adolescents working together to drive innovation and resolve pressing issues.

Also read: